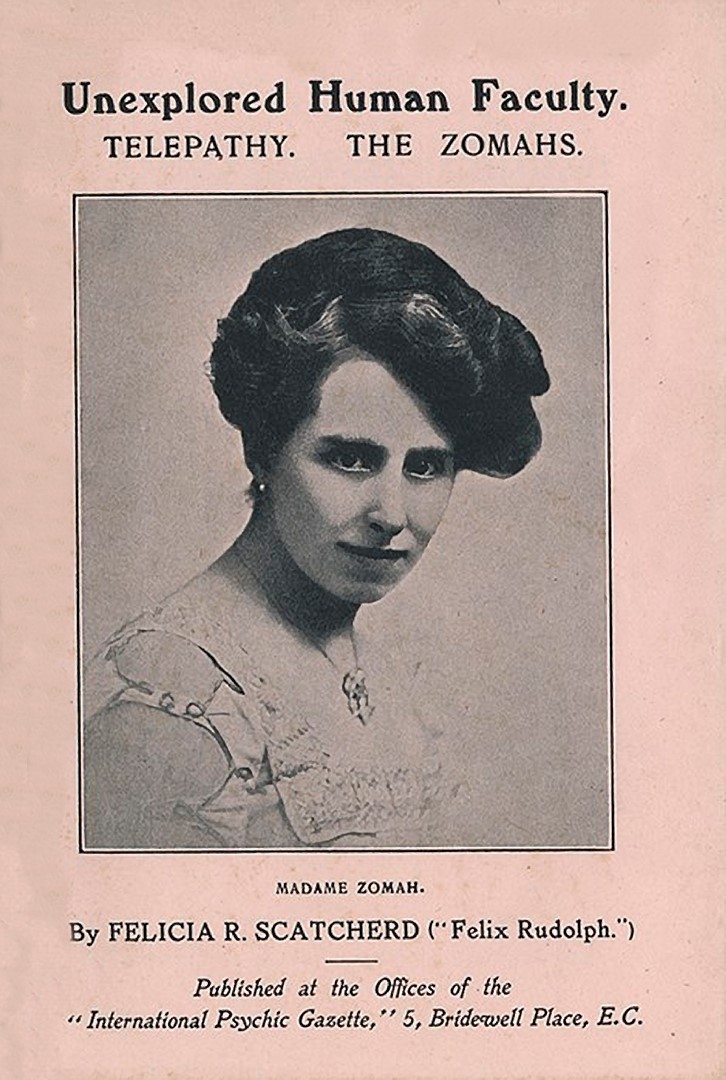

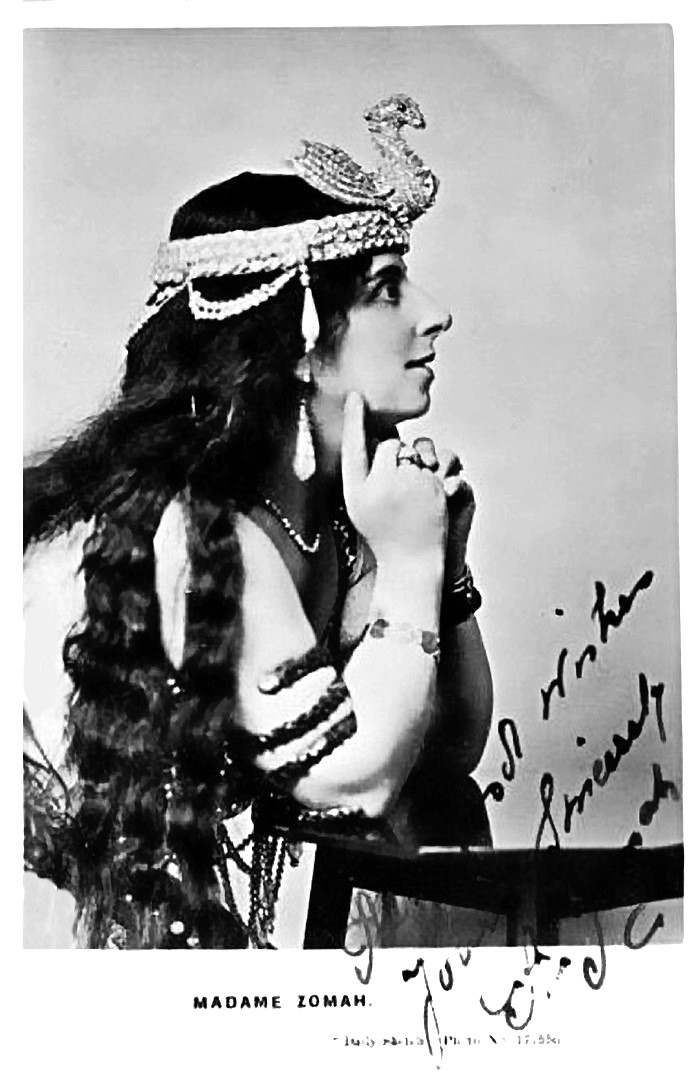

Madam Veda Zomah presented what was considered one of the most baffling telepathy acts in the theater. The act was billed as “The Unsolved Mystery.” The British couple originally billed themselves as the Marriotts. They worked at St. George’s Hall in 1908 under that name in an act called “The Technopathists.” This was before they went with an Egyptian theme. According to Adelaide (Madame Zomah), the new name was inspired by the Zancigs and by a subway ad she saw for an ointment named “Zam-buck.”

It was a partner act with her husband, but he stayed mostly in the background. He blindfolded her as she sat in an ornate chair, went into the audience, and held up objects that she identified. There was no verbal code though. Her husband remained silent. He was magician Alfred James Giddings (1879-1948), and Madame Zomah was Adelaide Ellen Giddings.

That Alfred was in the background can be seen in a number of newspaper articles I tracked down. In the Straits Times from January 1930, she is called Madame Zomah but Alfred is referred to as Mr. Marriott, her assistant. In the Jamaica Gleaner in February 1937, the headline is “Madame Zomah, World Famous Telepathist, And Her Husband, To Present Wonder Act.” The focus remains on Madame Zomah in this 1919 article from The Sketch titled “The Woman of Mystery”: “But Madame Zomah does not claim to read everybody’s thoughts, which is a relief, but those of Mr. Zomah, who acts as a medium in all her experiments.” I keep pointing this out as this is unusual to see the woman in the act being given all the credit.

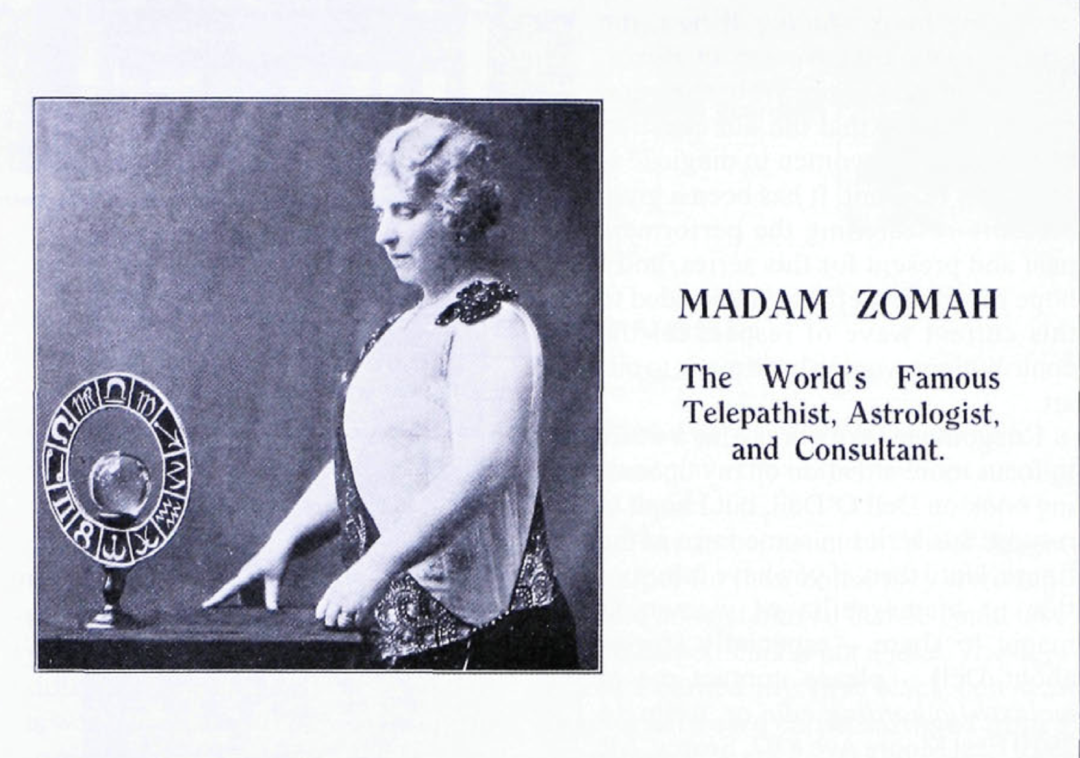

I also found a few descriptions of the act. She was able to read the serial number off a bill, and divined dates of birth. Audience members shuffled a pack of cards and dealt out hands. Madame Zomah knew all the cards and directed the play. In a 1912 article in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, where they typically believed that magicians had psychic powers, Vincent Turvey discusses them doing telepathy over the phone.

From an article in The Evening Telegraph and Post for March 13th, 1917:

The usual charge of using a code rather than depending on genuine transmission of thought which is leveled against very many exponents of so-called telepathy cannot attach to the performance of Madame Zomah who tops the bill at the King’s Theatre this week.

From Will Goldston’s The Magazine of Magic (July, 1917):

A Code? You watch for it, listen for it, guess at it. You discover nothing; after a moment’s consideration you reject every guess. The assistant makes no signal to Zomah; he speaks no word to her save the simple request for information and the acknowledgment that the information is correct.’ And goes on to say, ‘Zomah is offering big cash rewards to anybody who can duplicate her performance or can prove that she employs confederates.’

That offer led to a well publicized trial when magician John Clucas Cannell took up the offer in 1933 and published what he thought was the secret in an article “Famous Music Hall Secrets Exposed.” The Giddings sued and went to court in 1935. It was a complicated trial in that Cannell claimed that Mr. Giddings had violated his Magic Circle oath and revealed it to him. This added an additional charge of defamation.

In court Giddings refused to reveal the secret, stating that even when the King asked him to reveal the secret he refused. The Secretary of the Magic Circle testified on their behalf, along with famous magicians such as Horace Golden and Murray.

Amazingly, despite never revealing their secret, the Giddings won. Mrs. Giddings was awarded 250 pounds. Mr. Giddings was awarded 500 pounds. Some things never seem to change. They also got business damages, for a total of the equivalent to about $70,000 today. From the trial we also learn what they were making, which was around $190,000 a year in today’s dollars, which is not bad for a Music Hall act. The actual workings of the act died with them.

Most of this information comes from David Britland’s excellent Cardoplis blog. He also unearthed information about Adelaide’s sister, Ethelbertine. Could she have been in on the act? It turns out that she was a also a magician. In an article by Francis White in Goldston’s The Magician Monthly (April, 1936), there is a description of Ethelbertine performing a card location routine while blindfolded at The Institute of Magicians show.